Vintage Theory

Exploring Ancient OpeningsLong before Fischer, Lasker, or even Philidor, a Sicilian priest named Pietro Carrera wrote one of the earliest and most detailed books on chess. His work, first published in 1617, covers everything from openings and strategy to chess philosophy—and even includes a new version of the game with extra pieces. I have the 1822 first edition English translation, which only includes the parts the editor (W. Lewis) thought would be useful for players—mostly openings and something called Games of Odds. That might sound weird now, but back then it was common for stronger players to give handicaps, like removing a knight or letting the other player move first a few times, a bit like LeelaKnightOdds today. In this post, I want to take a closer look at Carrera’s ideas and focus on how regular chess theory has evolved over the last 400 years. The first interesting thing he says is that the only acceptable moves for white are 1.c4, d4, e4 and f4. He completely disregards 1.Nf3 and I think in general he was against making knight moves early on in the opening.

The King's Gambit

He begins by looking at 1.e4, and the main opening he covers is the King's Gambit, which was quite popular at the time. He writes:

“Various are the opinions of good players respecting the King's Gambit.”

Some say Black shouldn't take the pawn. Others say they should take it, but not try to hold it. A few say Black should take it and try to hold it.

Carrera believes Black should take the pawn and keep it, but they need to be very precise. He says it's easy for Black to fall behind quickly. When two strong players play, Black may even have an edge because they can defend accurately. But when two "moderately skilful" players play, White often benefits, since Black tends to misplay the defense, either losing the pawn or ending up with a bad position.

This is obviously a basic conclusion, but still surprisingly accurate. The King's Gambit isn't seen much at the top level today, but it's very dangerous if Black doesn't know how to respond.

The Queen's Gambit

In 1.d4, he talks about the Queen's Gambit and gives this advice: after 1.d4 d5 2.c4, Black should not take on c4 but instead play c6. He says if 2...dxc4 and White replies with e4, then White has “an excellent game.” He also says that after 1.d4, the moves 1...c6, d6, or e6 are acceptable if Black wants a closed game. It makes sense why he thought dxc4 was bad - visually, it gives White a big center and fast development, however modern engines show that it's fine.

English (1.c4) & Birds (1.f4)

On the English Opening, he says Black's best reply is 1...e5, while c5 and f5 are acceptable too. Against the Bird, he recommends 1...d5, and says 1...f5 is also decent. These are basic but reasonable conclusions. These lines probably weren’t very popular compared to 1.e4 and 1.d4, so it's understandable he doesn't go into much detail.

Below are some lines he gives in 1.e4 and 1.d4, obviously when you check with the engine most it will be rubbish. I haven't included everything but I think this illustrates his ideas well enough. The book is fully written old notation so it was a task to even convert these few lines haha

You may also like

FM PseudoBenko

FM PseudoBenkoVintage Problems

Positions from a 100+ year old book CM HGabor

CM HGaborHow titled players lie to you

This post is a word of warning for the average club player. As the chess world is becoming increasin… FM MathiCasa

FM MathiCasaChess Football: A Fun and Creative Variant

Where chess pieces become "players" and the traditional chessboard turns into a soccer field Mcie

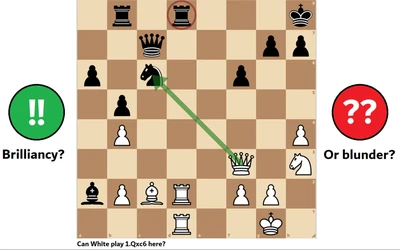

McieCalculate until the end.. and one move more!

Blunder or brilliancy, sometimes it all hinges on one more move. ChessMonitor_Stats

ChessMonitor_Stats